Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Barnes Foundation?

Why Is the Barnes Foundation in the News?

Why Is the Move a Bad Idea?

What Is the Current Status of The Barnes Foundation?

Who Wants to Move the Foundation?

Why Do They Want to Move It?

What Happened between the Barnes and Lincoln University?

Is there a Better Way?

Isn’t the Barnes Out of the Way and Difficult

to Get to?

Why Can’t I Get Into the Barnes?

Aren’t the Neighbors Hostile?

Why Was an Appeal Filed and What Did it Hope to Accomplish?

What Was the Outcome of the Appeal?

What is Special About the Barnes Foundation?

What is Special About the Education at Barnes?

Why is the Art Arranged in That Way on the Gallery Walls of the

Barnes Foundation?

What Is the Barnes Foundation?

The Barnes Foundation, in Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania, was

established in 1922 by Dr. Albert C. Barnes as an educational institution.

The art and horticulture collection, assembled by Albert Barnes and

his wife Laura, reflects their aesthetic concepts and are the principal

material of study.

The Barnes permanent art collection, housed in the gallery designed

for it by the renowned architect Paul Philippe Cret, includes 181

works by Renoir, 69 by Cezanne, and 60 by Matisse, as well as major

works by other twentieth century masters and significant collections

of African, Native American and American folk art.

The Arboretum contains over 2500 species and varieties of mature

trees and woody plants, many rare, as well as extensive collections

of herbaceous plants, including lilacs, peonies and ferns.

Read More...

Why Is the Barnes Foundation in the News?

The Barnes Foundation seeks to relocate its collection of art. According

to the Indenture of Trust established by Dr. Barnes to govern the

Foundation, its permanent art and horticulture collection and the

educational program associated with it are to remain in the historic

gallery and grounds created to house them. Pleading financial necessity,

the trustees of the Barnes Foundation petitioned the courts for permission

to move to an as-yet to be built facility in downtown Philadelphia.

Judge Stanley R. Ott granted the petition in December 2004.

The artistic, educational, and legal implications of the petition

have aroused worldwide interest and controversy. Nationally recognized

art critics, historians, and preservationists oppose the move.

top

Why Is the Move a Bad Idea?

1. Dr. Barnes established his Foundation as two schools, art and horticulture.

The material for the study of art is in its galleries, and for the

study of horticulture is in its arboretum. The two schools are interrelated,

and taken together, they create a unified whole that speaks to the

aesthetic principles that guide the Foundation.

Separating the art from its natural setting will destroy the interrelationship

that was set up by Dr. Barnes in his Indenture of Trust. The cavalier

decision by the courts of Pennsylvania to permit the violation of the

Trust will dissuade other charitable donors from granting important

gifts to the public. The disastrous precedent established in this case

continues to be discussed in the legal and philanthropic literature.

2. The rationale for violating the Trust is that it is the only means

to stabilize the Barnes’ finances and ensure its future. But

the Barnes’ own projected shortfall of revenue, once its own

plans for relocating the art and developing a three-campus site have

been realized, is four times the present deficit. The Barnes plan will

not make the Foundation more secure, but less so.

The fact is that the Foundation could survive in its present location

on a more modest budget and with a professional development program,

while fulfilling all the purposes of the Indenture of Trust. By neglecting

those purposes while promoting programs and activities never contemplated

by the Trust, it has created an artificial crisis in order to subvert

Dr. Barnes’ intentions and to destroy the Foundation he created.

3. The Foundation’s plan is grossly wasteful. It calls for a

commitment of $400 million to build a new facility in downtown Philadelphia

and establish an endowment. The final costs will surely be much higher.

They will drain desperately needed resources from the cash-starved

arts community in the Philadelphia region. There will be significant

costs as well to taxpayers.

Keeping the gallery art in Merion will cost the public nothing, and

would free up resources for other worthy arts and cultural projects.

4. The Barnes Foundation is, in the words of The New Yorker’s

art critic, Peter Schjeldahl, “a work of art in itself . . .

. Altering so much as a molecule of one of the greatest art installations

I have ever seen would be an aesthetic crime.” Relocating the

art would be such a crime.

‘Recreating’ the galleries as

part of a gargantuan facility in a congested urban environment would

be a mockery. Moving the contents of the art gallery would eviscerate

the experience that Albert Barnes intended to pass on to future generations--

an understanding and an appreciation of beauty in all its forms. To

remove one part of the Barnes Foundation would diminish the integrity

of the whole, destroy an irreplaceable cultural treasure and violate

the intention of its creator.

top

What Is the Current Status of The Barnes Foundation?

The Foundation remains in its original location in Lower Merion. In

December 2004, it was granted permission by the Orphans’ Court

of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, to relocate its gallery to a

facility to be built in downtown Philadelphia.

The decision of the

Orphans’ Court permits the relocation of the art but does not

order it. The Barnes Foundation, by all accounts, is going ahead

with its plan to move. Their timeline calls for construction to begin

within two years and for the new building to open in about four years.

top

Who Wants to Move the Foundation?

The move is principally supported by the trustees and administrators

of the Barnes Foundation, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Annenberg

Foundation, The Lenfest Foundation, the Mayor of Philadelphia, the

Governor of Pennsylvania, and the State Attorney General's Office.

Commercial interests also support the move.

top

Why Do They Want to Move It?

Proponents of the move claim that it is the only way to solve the Foundation’s

financial difficulties. They also claim that relocation of the art

collection will create greater public access to it. Commercial and

tourism interests expect to benefit from the move, and both local and

state governments hope to reap financial windfalls as well.

top

Is there a Better Way?

The Foundation has testified that the revenues generated by a $50 million

endowment would meet its current operating deficit. Its philanthropic

sponsors have pledged to put up such an amount in conjunction with

the move, but have refused to do so without it. In effect, they insist

on spending three dollars to compound a problem that a single dollar

would fix. Moreover, the Foundation’s deficit has been grossly

overstated, according to a court-commissioned audit by Deloitte and

Touche. In reality, the true deficit is half or less than that stated,

and could be covered by a $20-25 million endowment.

Evidence provided during the hearings proved that selling some of the

Foundation’s non-gallery assets in combination with raising the

admission fee will create an endowment and generate sufficient revenue

to cover their current operating shortfall. In addition, if the Foundation

ended its self-imposed boycott of approaching the Lower Merion Township,

it could negotiate in good faith for increased visitation.

The key is for those in charge at the Barnes Foundation to begin adhering

to Dr. Barnes’ intentions for his school and end their long and

self-bankrupting efforts to turn it into a something he did not intend.

top

Isn’t the Barnes Out of the Way and Difficult to Get

to?

No. The Foundation is conveniently served from downtown Philadelphia

by both bus and rail, and has facilities for reserved parking. It could

easily be linked by bus to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It takes

less time to travel from the Philadelphia Museum of Art to the Barnes

Foundation than it takes to get from the Philadelphia Museum of Art

to the Liberty Bell.

top

Why Can’t I Get Into the Barnes?

The administration of the Barnes Foundation makes it difficult. The

courts have ordered the Foundation to be open three days a week.

Many tickets are unclaimed each week because the Barnes has arbitrarily

decided not to admit persons without reservations. The statement

by Barnes spokesman Pete Peterson that the Foundation is not permitted

to accept walkup visitors by Township regulation, (The Philadelphia

Inquirer, March 29, 2005) is false. For decades the Barnes was open

to the first 100 persons in line, to visitors with reservations,

and to walkups as space permitted. There is no legal impediment to

reinstating such a policy.

top

Aren’t the Neighbors Hostile?

For over seventy years, the Barnes Foundation lived with its neighbors

in harmony and with mutual respect. When then-Director Richard Glanton

wished to promote the Foundation as a tourist destination after the

world tour of its collection, he created major traffic and safety

hazards for the neighborhood.

While attempts were being made to resolve these problems, the Barnes

Foundation filed a civil rights lawsuit under the Ku Klux Klan statute,

alleging racial discrimination against the Foundation by Township commissioners

and local residents. The U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed

the suit as “groundless” and “frivolous,” chastised

the Foundation for abusing the statute, and ordered it to pay the legal

fees of the neighbors.

The Barnes administration has falsely and repeatedly contended that

the neighbors had sued the Foundation. The only suit to be filed was

by the Foundation itself. Despite these continuing misrepresentations,

the Barnes’ neighbors regard the Foundation and its priceless

collection as a source of pride for the Lower Merion community. They

overwhelmingly support the retention of the collection at its present

site. Further, the Township Commissioners of Lower Merion passed a

Resolution opposing the move.

top

Why Was an Appeal Filed and What Did it Hope to Accomplish?

On January 11, 2005 an appeal from the Orphans' Court decisions was

filed by Jay Raymond, a current student and former member of the

faculty at Barnes.

It sought to overturn the Court's February 2003 denial of the right

to participate in the hearings as parties, i.e. standing, to Mr. Raymond

and other students. It also sought to appeal from the Orphans' Court

decision of December 2004 which drastically altered Dr. Barnes' Indenture

of Trust and granted permission to relocate the art.

If successful, these appeals could have prevented the irreparable harm

to the Foundation that the court’s decision will allow.

top

What Was the Outcome of the Appeal?

On April 27, 2005 Mr. Raymond's appeal was dismissed by the Pennsylvania

Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court ruled that the time to appeal from an order denying

permission to intervene as a party is within thirty days of the denial

of intervention, rather than within thirty days of the completion of

the entire proceedings. The Supreme Court also ruled that because Mr.

Raymond was not a party to the proceedings, due to the earlier denial

of intervention, he had no right of appeal from the final decisions

rewriting the Indenture and permitting the relocation of the art.

In so ruling, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania has clarified a previously

uncertain aspect of Pennsylvania procedural law. In 1992, the Pennsylvania

Rules of Appellate Procedure were substantially rewritten to provide

that in most instances, appeals from orders issued while a case remained

pending would need to await the resolution of the entire case. There

were some rare exceptions pursuant to which an immediate appeal could

be taken even in the absence of a final judgment in the case. But not

until the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided Mr. Raymond's appeal

was it established that an appeal from an order denying intervention

not only can but also must be taken within thirty days from the issuance

of the order or else appellate review will be precluded once the entire

case concludes.

top

What is Special About the Barnes Foundation?

Like an exquisite piece of jewelry, with precious gems laid out carefully

in a beautiful setting, the Barnes Foundation has qualities that

express the vision of its makers. In a very real sense, the whole

of the Foundation is greater than any of its separate parts. If you

change the setting, rearrange the jewels, and encapsulate the original

into a much larger piece, you end up with something that has little

relation to the original.

There is also a profound, intangible experience that awaits every visitor

to the Barnes Foundation. It is the realization of the unique vision

of Dr. Albert Barnes and his wife, Laura Barnes. His ideas formed the

art and hers the horticulture collection, and the Foundation is testament

to their thought processes and foresight. Working with major thinkers

of their day, including John Dewey and Bertrand Russell, the principle

idea is that there is an order and meaning to creative activity, no

matter when or from what culture, and that the order and meaning is

available to anyone who is given the tools to comprehend it. The gallery

and the arboretum are the evidence of their ideas: the school is the

laboratory where you learn how to investigate them yourself.

The gardens, the grounds, the buildings and the art provide the visitor

or the student with a gift that won’t be possible once the art

is transplanted to a busy city thoroughfare and then “cocooned’ inside

a vastly larger structure, separated from its green and peaceful setting.

top

What is Special About the Education at Barnes?

Dr. Barnes’ conviction was that the study of art must be rooted

in the forms that compose the works themselves, and the traditions

of the medium in which they are expressed. It avoids preoccupation

with extraneous biographical details about the artist or the social

and political climate that surround him/her. At the Barnes Foundation,

the galleries and the arboretum are the classrooms. The paintings,

other artwork, and the plants and trees are the direct and immediate

material of study.

The full value of the collection cannot be experienced by the casual

visitor to the galleries, or by the student in a classroom without

direct access to the collection. Yet, both of these claims are offered

by the present Barnes administration, which wants to promote casual

visitation as an end in itself, and to include a curriculum without

concurrent access to the art. They contradict Dr. Barnes’ vision

and undermine the meaning and intent of the collection, to whose assembly

and display he devoted such care.

top

Why is the Art Arranged in That Way on the Gallery Walls of

the Barnes Foundation?

by Harry Sefarbi

If a collection of books can be seen as a university (cf. Thomas Carlyle), a

collection of paintings can be seen as an art school, as evidenced by the walls

at the Barnes Foundation. Dr. Barnes recognized that art is as universal

as human nature, that art of all periods and places share broad human values

and aesthetic qualities. These principles are the basis for the objective

method of understanding art as developed by Dr. Barnes, John Dewey, and others.

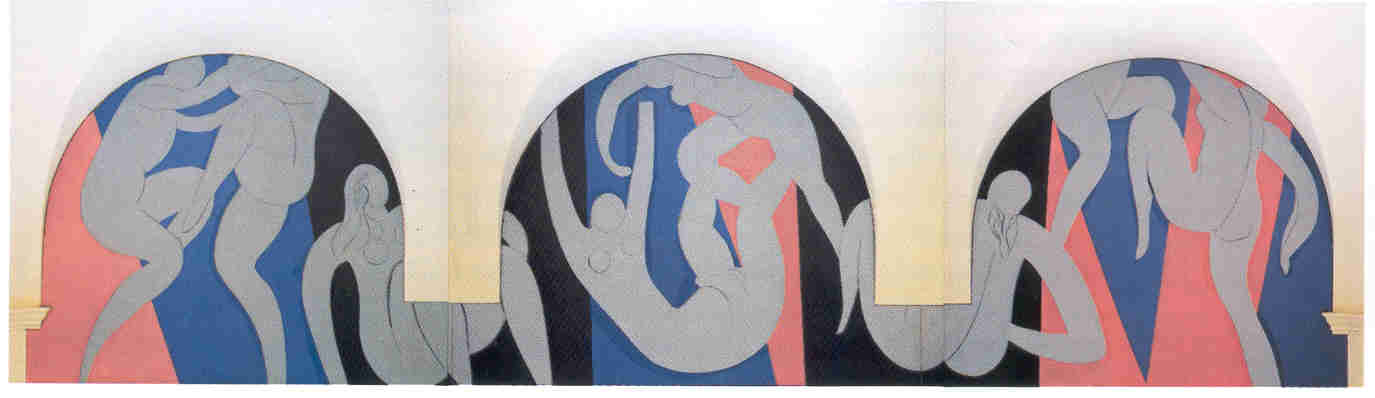

The paintings in the art gallery of the Barnes Foundation are hung to illustrate

aesthetic principles, and not, for example, according to historical periods

or by schools of painting. Hung in groups, basically pyramidal, the paintings

allow the viewer to compare the balanced units as to qualities, traditions, meanings.

In displaying the art collection, it was one of Dr. Barnes’s intentions

to demonstrate that aesthetic attributes may be appreciated wherever they are

found: the qualities that make paintings meaningful are the same qualities that

make everyday objects, and life itself, meaningful. The inclusion of the "hardware" and

other artifacts emphasizes this principle. Divorced from their functions,

the objects take their part in the wall ensembles: the hinges, escutcheons,

etc. are regarded for their aesthetic qualities. They are hung to dramatize

or underline some aspect of the paintings in their proximity: the keys on the

wall next to the Cezanne Card Players fall in line with the pipes on

the wall in the painting; the metal ornaments surrounding the Seurat Poseuses echo

its synthetic drawing.

At the Barnes Foundation, every wall may be understood as a particular "wall-picture."*

Just as a painter’s organization of his subject matter makes up his unique

creation, each wall ensemble is a unique creation, something never before seen

in that way, and like a painting, it makes its own point. The design of

the Renoir walls in Room XIII, with examples from each of his major periods,

is the recapitulation of his career. The groupings of the Cezanne Bathers and

Renoir Family in the main gallery, augmented by the Tintoretto Prophets and

the Giorgione portrait, share Venetian qualities of solid volumes in atmosphere-filled

space. On the opposite wall, the Seurat Poseuses and Cezanne’s Card

Players, flanked by the Rousseau Canal and the Prendergast Beach

Scene, become a triptych embodying qualities of early Italian painting. Room

XII, the "American Room," illustrates the variety of adopted influences

that make up the American tradition; e.g., the influence of Matisse on Glackens,

Fauvism on Maurer, Post-Impressionism on Prendergast.

As the examples in this paper convey, every room, object, artifact

and painting at the Barnes Foundation is fundamental to the design of its art display:

teaching people to see.

|

Harry Sefarbi |

|

December 2005 |

*"Wall-picture"– term used by

Violette de Mazia in her article The Barnes Foundation, |

|

The Display of its Art Collection, Vistas 1981-83,

The Barnes Foundation Press, Merion Station, Pa. |

© Harry Sefarbi 2005. No part of this paper

may be reproduced without permission of the author. |

top |